Microcontroller - A Beginners Guide - Adding a Button to the Microcontroller and

Making it Do Something

A very simple and easy way to provide for human interaction with the microcontroller

is to insert a button into the circuit. We communicate with computers using two

main input devices: the mouse and the keyboard. A keyboard is nothing more than

a bunch of buttons laid-out to allow the user to input (ASCII) characters to the

computer. If you're scratching your head on the ASCII part, don't worry--it just

represents the code for each character.

By this point in our journey, you should have already

setup your computer with WINAVR (or AVR-GCC for Linux), and be able to

program your microcontroller. You should also have a circuit built with

an LED plugged into the microcontroller. You

also made the LED blink in the previous

tutorial.

Adding

a button or switch to the circuit enables the microcontroller to receive human input.

Other forms of input for microcontrollers include (but are not limited to) a keyboard

or a mouse, buttons, switches, audio (through microphones), touch screen displays

and digitizers. There are of course many other devices that can provide input to

a microcontroller, but these may not all be activated by voluntary human action.

I place these other devices into the "sensing" category, as these devices typically

sense conditions or events and react accordingly. A few such examples include sensors

for tilt (accelerometers), detecting infrared energy or monitoring temperature.

Adding

a button or switch to the circuit enables the microcontroller to receive human input.

Other forms of input for microcontrollers include (but are not limited to) a keyboard

or a mouse, buttons, switches, audio (through microphones), touch screen displays

and digitizers. There are of course many other devices that can provide input to

a microcontroller, but these may not all be activated by voluntary human action.

I place these other devices into the "sensing" category, as these devices typically

sense conditions or events and react accordingly. A few such examples include sensors

for tilt (accelerometers), detecting infrared energy or monitoring temperature.

So, here's the skinny on buttons and mechanical switches: they're imperfect! The

two families of mechanics and electronics go together like the Montagues and Capulets.

That is, they don't! When you push a button, you might expect a clean response electronically.

Well, sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but the signal often bounces quite a bit

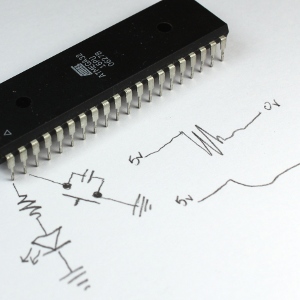

before it settles to its correct voltage level. In this image, I show this phenomenon.

If the voltage is set at 5 volts before the button is pressed and then goes to zero

volts when the button is pressed, there will be a "bouncing" effect of the voltage

between these two values. So then why don't all of our kitchen appliances or our

cars exhibit this problem?

As you should be able to see in the image, I have inserted a capacitor between the

two pins. This will smooth out the signal. The effect of this capacitor can be seen

on an oscilloscope, as demonstrated in the video. But if you don't have an oscilloscope

of your own, then you will just have to trust me. Another way we could alleviate

this problem is to add a time delay into the program, just after the microcontroller

senses the first button press event. However adding a discrete component to a circuit

to solve such an electronics problem, is often a better way than adding code to

cause a delay--as that code will introduce another potential source of a bug into

the program, and will also require more processor time to execute. In additional,

this code can also result in the development of other problems as the rest of the

code continues to execute.

But what value capacitor should we select? This will ultimately depend on how poorly

the button performs regarding this particular problem. Some buttons can display

a tremendous bouncing behavior, yet others will have very little. A low capacitor

value like 1.0nF (nanofarads) will react very quickly, with little or no effect

on the bouncing. Conversely, a higher capacitor value such as 220nF (which is still

pretty small in terms of capacitors) will provide a slow transition from the starting

to the ending voltage (i.e. 5v to 0v). The transition seen with a 220nF capacity

is still pretty fast in a real-world sense however, and thus can be used on poorly

performing buttons.

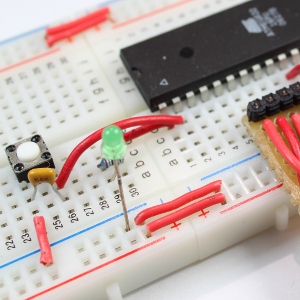

You

might have noticed by now that the breadboard has changed somewhat, to give the

circuit a cleaner look. The previous wires were too long, and the build environment

started getting messy as I added further components to the circuit. Therefore a

re-design of the breadboard was in order, so I snapped a second breadboard to the

end of the first. But you might be asking--why did I do this if there were sufficient

ties remaining at the other end? Well, I did it for neatness, and I also liked where

the microcontroller was positioned. You may be able to tell that I've aligned it

with the numbers so that I don't need to count pins all the time--I simply let the

breadboard numbering tell me where each pin is on the MCU. I also tied all of the

positive (+) rails on both boards together, and did the same to all of the negative

(-) rails as well. This will allow me to have VCC or GND close by, anywhere on the

breadboard.

You

might have noticed by now that the breadboard has changed somewhat, to give the

circuit a cleaner look. The previous wires were too long, and the build environment

started getting messy as I added further components to the circuit. Therefore a

re-design of the breadboard was in order, so I snapped a second breadboard to the

end of the first. But you might be asking--why did I do this if there were sufficient

ties remaining at the other end? Well, I did it for neatness, and I also liked where

the microcontroller was positioned. You may be able to tell that I've aligned it

with the numbers so that I don't need to count pins all the time--I simply let the

breadboard numbering tell me where each pin is on the MCU. I also tied all of the

positive (+) rails on both boards together, and did the same to all of the negative

(-) rails as well. This will allow me to have VCC or GND close by, anywhere on the

breadboard.

So then, how do we program the ATmega32 microcontroller (or other MCU that you may

be applying to this experiment) to make use of the new button? Well it's really

quite straightforward! We only have to add two initializing lines just prior to

the infinite loop, and a single condition block within the loop. The two initialization

lines added before the loop include one statement to set PINB1 for input by assigning

it a "0" like this:

DDRB &= ~(1 << PINB1);

We will also set pin B1 "high," meaning the pin will read 5 volts until the button

is pressed; at which time the pin will read zero volts. To set the pin at a high

voltage of 5 volts, we add this line of code:

PORTB |= 1 << PINB1;

Within the program, there must be a decision: a decision to run some code when the

button is pressed, or run some other code if the button is not pressed. This task

is in the form of a conditional statement called an "if else" statement. It does

EXACTLY what is says. Just like the English equivalent... if (the button is

pressed), jump up and down, else stand on your head.

the action "jump up and down" will happen while the button is pressed. But while

the button is not pressed, the other action "stand on your head" will happen. The

if statement code:

if (bit_is_clear(PINB, 1))

specifies a test for a condition specified inside the parentheses. The name "bit_is_clear"

represents a function that takes two arguments. In this case the first argument

is PINB, which describes the set of pins we are specifying. The second argument

represents which pin we are checking, and in this case we are concerned with pin

#1 in the set.

You might be wondering what sorts of things can we put into the code block controlled

by the "if" condition? That all depends on what you want your program (and circuit)

to do. In this case, as a way to show that this button does something and works,

I have the LED blinking slowly (every 100 ms) while the button is not pressed, and

blinking faster (every 10ms) while pressed.

Here are the changes made to the previous LED blinking program:

#include <avr/io.h>

#include <util/delay.h>

int main(void)

{

DDRB |= 1 << PINB0;

DDRB &= ~(1 << PINB1);

PORTB |= 1 << PINB1;

while (1)

{

PORTB ^= 1 << PINB0;

if (bit_is_clear(PINB, 1))

{

_delay_ms(10); //Fast

}

else

{

_delay_ms(100); //Slow, from previous

}

}

}

That is it!! There is very little programming required to use a button, LED and

make things blink!